برای محاسبه واریانس عدد های زیر را تغییر دهید

http://www.stanford.edu/~boyd/papers/admm/lasso/lasso_example.html

http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~susan/courses/b494/index/node35.html

http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~susan/courses/s227/node5.html

http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~susan/courses/b494/index/node29.html

lasso

Regularized least-squares regression using lasso or elastic net algorithms

Syntax

B = lasso(X,Y)

[B,FitInfo] = lasso(X,Y)

[B,FitInfo] = lasso(X,Y,Name,Value)

Description

B = lasso(X,Y) returns fitted least-squares regression coefficients for a set of regularization coefficients Lambda.

[B,FitInfo] = lasso(X,Y) returns a structure containing information about the fits.

[B,FitInfo] = lasso(X,Y,Name,Value) fits regularized regressions with additional options specified by one or more Name,Value pair arguments.

Input Arguments

Name-Value Pair Arguments

Specify optional comma-separated pairs of Name,Value arguments. Name is the argument name and Value is the corresponding value. Name must appear inside single quotes (' '). You can specify several name and value pair arguments in any order as Name1,Value1,...,NameN,ValueN.

| 'Alpha' | Scalar value from 0 to 1 (excluding 0) representing the weight of lasso (L1) versus ridge (L2) optimization. Alpha = ۱ represents lasso regression, Alpha close to 0 approaches ridge regression, and other values represent elastic net optimization. See Definitions.Default: 1 |

| 'CV' | Method lasso uses to estimate mean squared error:

Default: 'resubstitution' |

| 'DFmax' | Maximum number of nonzero coefficients in the model. lasso returns results only for Lambda values that satisfy this criterion.Default: Inf |

| 'Lambda' | Vector of nonnegative Lambda values. See Definitions.

Default: Geometric sequence of NumLambda values, the largest just sufficient to produce B = ۰ |

| 'LambdaRatio' | Positive scalar, the ratio of the smallest to the largest Lambda value when you do not set Lambda.If you set LambdaRatio = ۰, lasso generates a default sequence of Lambda values, and replaces the smallest one with 0.Default: 1e-4 |

| 'MCReps' | Positive integer, the number of Monte Carlo repetitions for cross validation.

Default: 1 |

| 'NumLambda' | Positive integer, the number of Lambda values lasso uses when you do not set Lambda. lasso can return fewer than NumLambda fits if the if the residual error of the fits drops below a threshold fraction of the variance of Y.Default: 100 |

| 'Options' | Structure that specifies whether to cross validate in parallel, and specifies the random stream or streams. Create the Options structure with statset. Option fields:

|

| 'PredictorNames' | Cell array of strings representing names of the predictor variables, in the order in which they appear in X.Default: {} |

| 'RelTol' | Convergence threshold for the coordinate descent algorithm (see Friedman, Tibshirani, and Hastie [3]). The algorithm terminates when successive estimates of the coefficient vector differ in the L2 norm by a relative amount less than RelTol.Default: 1e-4 |

| 'Standardize' | Boolean value specifying whether lasso scales X before fitting the models.Default: true |

| 'Weights' | Observation weights, a nonnegative vector of length n, where n is the number of rows of X. lasso scales Weights to sum to 1.Default: 1/n * ones(n,1) |

Output Arguments

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

%

% File: Lasso.m

% Author: Jinzhu Jia

%

% One simple (Gradiant Descent) implementation of the Lasso

% The objective function is:

% ۱/۲*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta))

% Comparison with CVX code is done

% Reference: To be uploaded

%

% Version 4.23.2010

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

function [beta0,beta] = Lasso(X,Y,lambda)

n = size(X,1);

p = size(X,2);

if(size(Y,1) ~= n)

fprintf( ‘Error: dim of X and dim of Y are not match!!\n’)

quit cancel

end

beta0 = 0;

beta= zeros(p,1);

crit = 1;

step = 0;

while(crit > 1E-5)

step = step + 1;

obj_ini = 1/2*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta));

beta0 = mean(Y – X*beta);

for(j = 1:p)

a = sum(X(:,j).^2);

b = sum((Y – X*beta).* X(:,j)) + beta(j) * a;

if lambda >= abs(b)

beta(j) = 0;

else

if b>0

beta(j) = (b – lambda) / a;

else

beta(j) = (b+lambda) /a;

end

end

end

obj_now = 1/2*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta));

crit = abs(obj_now – obj_ini) / abs(obj_ini);

end

————————————————————————-

%% Lasso regularization example

% Copyright (c) 2011, The MathWorks, Inc.

%% Introduction to using LASSO

using the lasso functionality introduced

% in R2011b. It is motivated by

% This demo explains how to star

tan example in Tibshiranis original paper

% on the lasso.

via the lasso.

% J. Royal. Statist. Soc B., Vol. 58, No. 1, pages 267-288)

% Tibshirani, R. (1996). Regression shrinkage and selection . % The data set that were working with in this demo is a wide

ferent

% variables and only 20 observations. 5 out of the 8 variables h

% dataset with correlated variables. This data set includes 8 di fave % coefficients of zero. These variables have zero impact on the model. The

up workspace and set random seed

clear all

clc

% Set the random num

% other three variables have non negative values and impact the model %% Clean ber stream rng(1981); %% Creating data set with specific characteristics % Create eight X variables

with one another

% The covariance matrix is spec

% The mean of each variable will be equal to zero mu = [0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]; % The variable are correlate dified as i = 1:8; matrix = abs(bsxfun(@minus,i',i)); covariance = repmat(.5,8,8).^matrix;

, covariance, 20);

% Create a hyperplane that describes Y = f(X)

Beta = [3; 1

% Use these parameters to generate a set of multivariate normal random numbers X = mvnrnd(m u.5; 0; 0; 2; 0; 0; 0]; ds = dataset(Beta); % Add in a noise vector Y = X * Beta + 3 * randn(20,1); %% Use linear regression to fit the model b = regress(Y,X);

s, ‘PlotType’,

ds.Linear = b; %% Use a lasso to fit the model [B Stats] = lasso(X,Y, 'CV', 5); disp(B) disp(Stats) %% Create a plot showing MSE versus lamba lassoPlot(B, Sta t 'CV') %% Identify a reasonable set of lasso coefficients % View the regression coefficients associated with Index1SE ds.Lasso = B(:,Stats.Index1SE); disp(ds)

(۱۰۰,۱);

Coeff_Num = zeros(100,1);

Betas = zeros(8,100);

cv

%% Create a plot showing coefficient values versus L1 norm

lassoPlot(B, Stats)

%% Run a Simulation

% Preallocate some variables

MSE = zeros(100,1);

mse = zero

s_Reg_MSE = zeros(1,100);

for i = 1 : 100

X = mvnrnd(mu, covariance, 20);

Y = X * Beta + randn(20,1);

[B Stats] = lasso(X,Y, 'CV', 5);

E(i) = Stats.MSE(:, Shrink);

regf = @(XTRAIN, ytrain, XTEST)(XTEST*

Shrink = Stats.Index1SE - ceil((Stats.Index1SE - Stats.IndexMinMSE)/2);

Betas(:,i) = B(:,Shrink) > 0;

Coeff_Num(i) = sum(B(:,Shrink) > 0);

M

Sregress(ytrain,XTRAIN));

cv_Reg_MSE(i) = crossval('mse',X,Y,'predfun',regf, 'kfold', 5);

end

Number_Lasso_Coefficients = mean(Coeff_Num);

disp(Number_Lasso_Coefficients)

MSE_Ratio = median(cv_Reg_MSE)/median(MSE);

disp(MSE_Ratio)

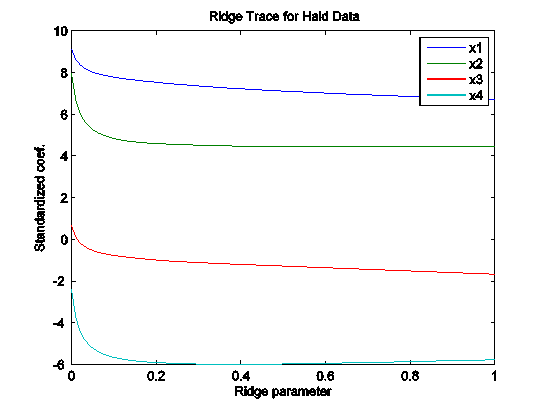

توضیح رگرسیون ریج :

مقیاسی که میخواهیم مینیمم کنیم مجموع مربعات خطا است

به شرطی که مجموع مربعات ضرایب از یک مقداری کوچکتر باشد

معادل این است که این کمیت را می نیمم کنیم

لاندا همان ضریب لاگرانژ است

load hald

k = 0:.01:1;

b = ridge(heat, ingredients, k);

plot(k, b’);

xlabel(‘Ridge parameter’); ylabel(‘Standardized coef.’);

title(‘Ridge Trace for Hald Data’)

legend(‘x1′,’x2′,’x3′,’x4’);

clear all;

close all;

x=randn(2,100);

x(2,:)=-5*x(1,:)+4+2*randn(1,100);

x=x’;

Y=x(:,2);

X=[x(:,1)];

%[b,bint,R,Rint,stats]=regress(Y,X);

k=0;

for lambda=0:.1:10

k=k+1;

b=ridge(Y,X,lambda,0);

Yhat=X*b(2:end)+b(1);

R=Y-Yhat;

% plot(x(:,1),Y,’*g’)

% hold on

% plot(x(:,1),R,’+r’)

sse(k)=R’*R;

end

Ridge regression

Syntax

b = ridge(y,X,k)

b = ridge(y,X,k,scaled)

Description

b = ridge(y,X,k) returns a vector b of coefficient estimates for a multilinear ridge regression of the responses in y on the predictors in X. X is an n-by-p matrix of p predictors at each of n observations. y is an n-by-1 vector of observed responses. k is a vector of ridge parameters. If k has m elements, b is p-by-m. By default, b is computed after centering and scaling the predictors to have mean 0 and standard deviation 1. The model does not include a constant term, and X should not contain a column of 1s.

b = ridge(y,X,k,scaled) uses the {0,1}-valued flag scaled to determine if the coefficient estimates in b are restored to the scale of the original data. ridge(y,X,k,0) performs this additional transformation. In this case, b contains p+1 coefficients for each value of k, with the first row corresponding to a constant term in the model. ridge(y,X,k,1) is the same as ridge(y,X,k). In this case, b contains p coefficients, without a coefficient for a constant term.

The relationship between b0 = ridge(y,X,k,0) and b1 = ridge(y,X,k,1) is given by

m = mean(X);

s = std(X,0,1)';

b1_scaled = b1./s;

b0 = [mean(y)-m*temp; b1_scaled]

This can be seen by replacing the xi (i = ۱, …, n) in the multilinear model y = b00 + b10x1 + … + bn0xn with the z-scores zi = (xi – μi)/σi , and replacing y with y – μy.

In general, b1 is more useful for producing plots in which the coefficients are to be displayed on the same scale, such as a ridge trace (a plot of the regression coefficients as a function of the ridge parameter). b0 is more useful for making predictions.

Coefficient estimates for multiple linear regression models rely on the independence of the model terms. When terms are correlated and the columns of the design matrix X have an approximate linear dependence, the matrix (XTX)–۱ becomes close to singular. As a result, the least squares estimate

![]()

becomes highly sensitive to random errors in the observed response y, producing a large variance. This situation of multicollinearity can arise, for example, when data are collected without an experimental design.

Ridge regression addresses the problem by estimating regression coefficients using

![]()

where k is the ridge parameter and I is the identity matrix. Small positive values of k improve the conditioning of the problem and reduce the variance of the estimates. While biased, the reduced variance of ridge estimates often result in a smaller mean square error when compared to least-squares estimates.

Example

Load the data in acetylene.mat, with observations of the predictor variables x1, x2, x3, and the response variable y:

load acetylene

Plot the predictor variables against each other:

subplot(1,3,1)

plot(x1,x2,'.')

xlabel('x1'); ylabel('x2'); grid on; axis square

subplot(1,3,2)

plot(x1,x3,'.')

xlabel('x1'); ylabel('x3'); grid on; axis square

subplot(1,3,3)

plot(x2,x3,'.')

xlabel('x2'); ylabel('x3'); grid on; axis square

Note the correlation between x1 and the other two predictor variables.

Use ridge and x2fx to compute coefficient estimates for a multilinear model with interaction terms, for a range of ridge parameters:

X = [x1 x2 x3]; D = x2fx(X,'interaction'); D(:,1) = []; % No constant term k = 0:1e-5:5e-3; b = ridge(y,D,k);

Plot the ridge trace:

figure

plot(k,b,'LineWidth',2)

ylim([-100 100])

grid on

xlabel('Ridge Parameter')

ylabel('Standardized Coefficient')

title('{\bf Ridge Trace}')

legend('constant','x1','x2','x3','x1x2','x1x3','x2x3')

The estimates stabilize to the right of the plot. Note that the coefficient of the x2x3 interaction term changes sign at a value of the ridge parameter ≈ ۵ × ۱۰–۴.

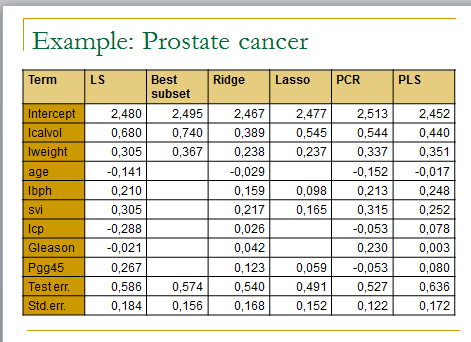

## Practical session: Linear regression

## Jean-Philippe.Vert@mines.org

##

## In this practical session to test several linear regression methods on the prostate cancer dataset

##

####################################

## Prepare data

####################################

# Download prostate data

con = url (“http://www-stat.stanford.edu/~tibs/ElemStatLearn/datasets/prostate.data”)

prost=read.csv(con,row.names=1,sep=”\t”)

# Alternatively, load the file and read from local file as follows

# prost=read.csv(‘prostate.data.txt’,row.names=1,sep=”\t”)

# Scale data and prepare train/test split

prost.std <- data.frame(cbind(scale(prost[,1:8]),prost$lpsa))

names(prost.std)[9] <- ‘lpsa’

data.train <- prost.std[prost$train,]

data.test <- prost.std[!prost$train,]

y.test <- data.test$lpsa

n.train <- nrow(data.train)

####################################

## Ordinary least squares

####################################

m.ols <- lm(lpsa ~ . , data=data.train)

summary(m.ols)

y.pred.ols <- predict(m.ols,data.test)

summary((y.pred.ols – y.test)^2)

# the importance of a feature depends on other features. Compare the following. Explain (visualize).

summary(lm(lpsa~svi,data=datatrain))

summary(lm(lpsa~svi+lcavol,data=datatrain))

####################################

## Best subset selection

####################################

library(leaps)

l <- leaps(data.train[,1:8],data.train[,9],method=’r2′)

plot(l$size,l$r2)

l <- leaps(data.train[,1:8],data.train[,9],method=’Cp’)

plot(l$size,l$Cp)

# Select best model according to Cp

bestfeat <- l$which[which.min(l$Cp),]

# Train and test the model on the best subset

m.bestsubset <- lm(lpsa ~ .,data=data.train[,bestfeat])

summary(m.bestsubset)

y.pred.bestsubset <- predict(m.bestsubset,data.test[,bestfeat])

summary((y.pred.bestsubset – y.test)^2)

####################################

## Greedy subset selection

####################################

library(MASS)

# Forward selection

m.init <- lm(lpsa ~ 1 , data=data.train)

m.forward <- stepAIC(m.init, scope=list(upper=~lcavol+lweight+age+lbph+svi+lcp+gleason+pgg45,lower=~1) , direction=”forward”)

y.pred.forward <- predict(m.forward,data.test)

summary((y.pred.forward – y.test)^2)

# Backward selection

m.init <- lm(lpsa ~ . , data=data.train)

m.backward <- stepAIC(m.init , direction=”backward”)

y.pred.backward <- predict(m.backward,data.test)

summary((y.pred.backward – y.test)^2)

# Hybrid selection

m.init <- lm(lpsa ~ 1 , data=data.train)

m.hybrid <- stepAIC(m.init, scope=list(upper=~lcavol+lweight+age+lbph+svi+lcp+gleason+pgg45,lower=~1) , direction=”both”)

y.pred.hybrid <- predict(m.hybrid,data.test)

summary((y.pred.hybrid – y.test)^2)

####################################

## Ridge regression

####################################

library(MASS)

m.ridge <- lm.ridge(lpsa ~ .,data=data.train, lambda = seq(0,20,0.1))

plot(m.ridge)

# select parameter by minimum GCV

plot(m.ridge$GCV)

# Predict is not implemented so we need to do it ourselves

y.pred.ridge = scale(data.test[,1:8],center = F, scale = m.ridge$scales)%*% m.ridge$coef[,which.min(m.ridge$GCV)] + m.ridge$ym

summary((y.pred.ridge – y.test)^2)

####################################

## Lasso

####################################

library(lars)

m.lasso <- lars(as.matrix(data.train[,1:8]),data.train$lpsa)

plot(m.lasso)

# Cross-validation

r <- cv.lars(as.matrix(data.train[,1:8]),data.train$lpsa)

bestfraction <- r$fraction[which.min(r$cv)]

##### Note 5/8/11: in the new lars package 0.9-8, the field r$fraction seems to have been replaced by r$index. The previous line should therefore be replaced by:

# bestfraction <- r$index[which.min(r$cv)]

# Observe coefficients

coef.lasso <- predict(m.lasso,as.matrix(data.test[,1:8]),s=bestfraction,type=”coefficient”,mode=”fraction”)

coef.lasso

# Prediction

y.pred.lasso <- predict(m.lasso,as.matrix(data.test[,1:8]),s=bestfraction,type=”fit”,mode=”fraction”)$fit

summary((y.pred.lasso – y.test)^2)

####################################

## PCR

####################################

library(pls)

m.pcr <- pcr(lpsa ~ .,data=data.train , validation=”CV”)

# select number of components (by CV)

ncomp <- which.min(m.pcr$validation$adj)

# predict

y.pred.pcr <- predict(m.pcr,data.test , ncomp=ncomp)

summary((y.pred.pcr – y.test)^2)

####################################

## PLS

####################################

library(pls)

m.pls <- plsr(lpsa ~ .,data=data.train , validation=”CV”)

# select number of components (by CV)

ncomp <- which.min(m.pls$validation$adj)

# predict

y.pred.pcr <- predict(m.pls,data.test , ncomp=ncomp)

summary((y.pred.pcr – y.test)^2)

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

%

% File: Lasso.m

% Author: Jinzhu Jia

%

% One simple (Gradiant Descent) implementation of the Lasso

% The objective function is:

% ۱/۲*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta))

% Comparison with CVX code is done

% Reference: To be uploaded

%

% Version 4.23.2010

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

function [beta0,beta] = Lasso(X,Y,lambda)

n = size(X,1);

p = size(X,2);

if(size(Y,1) ~= n)

fprintf( ‘Error: dim of X and dim of Y are not match!!\n’)

quit cancel

end

beta0 = 0;

beta= zeros(p,1);

crit = 1;

step = 0;

while(crit > 1E-5)

step = step + 1;

obj_ini = 1/2*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta));

beta0 = mean(Y – X*beta);

for(j = 1:p)

a = sum(X(:,j).^2);

b = sum((Y – X*beta).* X(:,j)) + beta(j) * a;

if lambda >= abs(b)

beta(j) = 0;

else

if b>0

beta(j) = (b – lambda) / a;

else

beta(j) = (b+lambda) /a;

end

end

end

obj_now = 1/2*sum((Y – X * beta -beta0).^2) + lambda * sum(abs(beta));

crit = abs(obj_now – obj_ini) / abs(obj_ini);

end

مثال خروجی :

رگرسیون چند متغیره، یکی از متدهای آماری مقدماتی جهت پیش بینی روند متغییری وابسته به دو یا چند متغیر مستقل است.

از این روش میتوان برای تصمیم گیری در مورد خرید های پروژه استفاده های زیادی کرد. به عنوان مثال میتوان عادلانه بودن قیمت پیشنهادی برای یکی از ماشین آلات دست دوم را مورد بررسی قرار داد.

به این صورت که قیمت را در دوره های گذشته برای ماشین های مشابه با متغیرهای متفاوت، ( مثلاً مدت کارکرد و مدل ماشین ) مورد بررسی قرار داده و تابع قیمت را بر اساس فاکتورهای مدت کارکرد و مدل تخمین زد.

میزان انحراف قیمت پیشنهادی از قیمت تخمین زده شده توسط تکنیک رگرسیون خطی چند متغیره میتواند شاخص مناسبی در تصمیم گیری جهت خرید باشد.

رگرسیون درmatlab به صورت های زیر تعریف شده است.

xreglinear/regression

REGRESSION returns the regression matrix for the model m

[r,ok]=regression(m)

function [r,ok]=regression(m)

%REGRESSION returns the regression matrix for the model m

%

% [r,ok]=regression(m)

% Copyright 2000-2007 The MathWorks, Inc. and Ford Global Technologies, Inc.

% $Revision: 1.2.2.3 $ $Date: 2007/06/18 22:38:40 $

if ~isfield(m.Store,’Q’)

error(‘mbc:xreglinear:InvalidState’,…

‘Use InitStore first to initialize data in model’);

end

r=m.Store.X;

if ~isempty(r)

r=r(:,terms2(m));

end

if nargout>1

% rank check on regression matrix

ok=~(rank(r)

end

localsurface/regression

r=REGRESSION(m) returns the regression matrix for the model m

function [r,ok]=regression(m)

% r=REGRESSION(m) returns the regression matrix for the model m

% Copyright 2000-2004 The MathWorks, Inc. and Ford Global Technologies, Inc.

% $Revision: 1.2.2.2 $ $Date: 2004/02/09 07:42:28 $

[r,ok]=regression(m.userdefined);

لازم به ذکر است که تابع رگرسیون به صورت doubleکار میکند وبصورت زیر فراخوانی میشود.

R =regression(m)

اما ما میتوانیم تابع مورد نظرمان را با انتخاب گزینه ی file>>new>>…..و هر یک از گزینه های new، تعریف کنیم.

برای استفاده از تابع Ridge :

X = [x1 x2 x3];

D = x2fx(X,’interaction’);

D(:,1) = []; % No constant term

k = 0:1e-5:5e-3;

b = ridge(y,D,k);

Plot the ridge trace:

figure

plot(k,b,’LineWidth’,2)

ylim([-100 100])

grid on

xlabel(‘Ridge Parameter’)

ylabel(‘Standardized Coefficient’)

title(‘{\bf Ridge Trace}’)

legend(‘x1′,’x2′,’x3′,’x1x2′,’x1x3′,’x2x3’)

———————————————-

مثالی از رگرسیون ریج

Example of a matlab ridge regression function:

function bks=ridge(Z,Y,kvalues)

% Ridge Function of Z (centered, explanatory)

% Y is the response,

es where to compute

[n,p]=size(Z);

ZpY=Z’

% kvalues are the val

u*Y;

ZpZ=Z’*Z;

m=length(kvalues);

bks=ones(p,m);

for k =1:m

.۵)

kvalues =

Columns 1 through 7

bks(:,k)=(ZpZ+diag(kvalues(k)))\ZpY;

end

values=(0:.05

>> k

: ۰ ۰٫۰۵۰۰ ۰٫۱۰۰۰ ۰٫۱۵۰۰ ۰٫۲۰۰۰ ۰٫۲۵۰۰ ۰٫۳۰۰۰

Columns 8 through 11

۱٫۵۵۱۱ ۱٫۵۱۷۶ ۱٫۴۸۸۲ ۱٫۴۶۲۲

۰٫۳۵۰۰ ۰٫۴۰۰۰ ۰٫۴۵۰۰ ۰٫۵۰۰۰

>> ridge(Z,Y,(0:.05:.5))

ans =

Columns 1 through 7

۱٫۴۳۹۰ ۱٫۴۱۸۳ ۱٫۳۹۹۶

۰٫۵۱۰۲ ۰٫۴۷۷۵ ۰٫۴۴۸۸ ۰٫۴۲۳۴ ۰٫۴۰۰۹ ۰٫۳۸۰۶ ۰٫۳۶۲۴

-۰٫۲۲۹۲ -۰٫۲۵۱۴ -۰٫۲۷۱۳ -۰٫۲۸۹۲

Columns 8 through 11

۱٫

۰٫۱۰۱۹ ۰٫۰۶۷۸ ۰٫۰۳۷۸ ۰٫۰۱۱۳ -۰٫۰۱۲۲ -۰٫۰۳۳۴ -۰٫۰۵۲۴

-۰٫۱۴۴۱ -۰٫۱۷۶۲ -۰٫۲۰۴۳

۳۸۲۷ ۱٫۳۶۷۳ ۱٫۳۵۳۲ ۱٫۳۴۰۳

۰٫۳۴۵۹ ۰٫۳۳۰۹ ۰٫۳۱۷۲ ۰٫۳۰۴۶

-۰٫۰۶۹۶ -۰٫۰۸۵۳ -۰٫۰۹۹۷ -۰٫۱۱۲۸

-۰٫۳۰۵۴ -۰٫۳۲۰۱ -۰٫۳۳۳۶ -۰٫۳۴۶۰

۲٫۶۹۷۳

>> k=(4*5.9829)/2.6973

%Formula gives for choice of k:

>> norm(Yhat-Yc)^2

ans =

۴۷٫۸۶۳۶

>> 47.8636/(13-5)

ans =

۵٫۹۸۲۹ % estimates the variance sigma^2

>> bk0'*bk0

ans =

k =

.۸۷۲۴ % This is a suggested value for k

۸

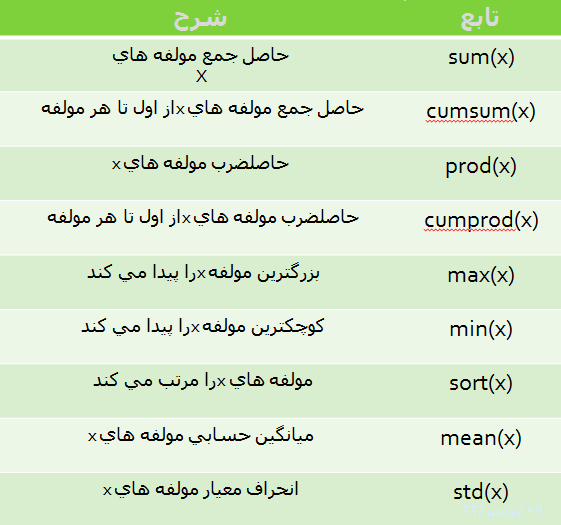

نکاتی درباره کار با نرم افزار متلب

روش اول تعریف کردن بردارها

» v=[1 2 3]

v =

۱ ۲ ۳

» w=[‘abcd’ ‘1234’]

w =

abcd1234

-

برای تعریف بردارهای عددی حتما” باید از کروشه استفاده کرد ولی استفاده از آنها برای متغیرهای حرفی الزامی نیست.

- حالت خاصی از بردار عبارتست از بردار تهی که به صورت [ ] تعریف می گردد.

روش دوم تعریف کردن بردارها

» x = 0:4

x=

۰ ۱ ۲ ۳ ۴

» x = (0:0.2:1)

x =

۰ ۰٫۲ ۰٫۴ ۰٫۶ ۰٫۸ ۱

عملیات ماتریسی روی آرایه ها

در MATLAB می توان دو نوع عملیات روی آرایهها انجام داد که به آنها عملیات ماتریسی و عملیات عضو به عضو می گویند.

عملیات ماتریسی شامل محاسبه ترانهاده، ضرب ماتریسی، جمع و تفریق آرایه های هم اندازه و غیره می شود.

» m=[1 2 3

۴ ۵ ۶];

» ۲*m

ans =

۲ ۴ ۶

۸ ۱۰ ۱۴

یا

» m+1

ans =

۲ ۳ ۴

۵ ۶ ۸

» r=rand(2,4)

r =

۰٫۹۵۰۱ ۰٫۶۰۶۸ ۰٫۸۹۱۳ ۰٫۴۵۶۵

۰٫۲۳۱۱ ۰٫۴۸۶۰ ۰٫۷۶۲۱ ۰٫۰۱۸۵

» r’

ans =

۰٫۹۵۰۱ ۰٫۲۳۱۱

۰٫۶۰۶۸ ۰٫۴۸۶۰

۰٫۸۹۱۳ ۰٫۷۶۲۱

۰٫۴۵۶۵ ۰٫۰۱۸۵

» r=rand(2,4);

» v=[1:4];

» r*v’

ans =

۶٫۶۶۳۶

۳٫۵۶۳۴

چندجملهایها

یک چند جملهای در MATLAB به صورت یک بردار سطری که مولفه های آن ضرایب چندجمله ای به ترتیب نزولی هستند معرفی می شود.

این نرم افزار قابلیت محاسبهی ریشه های یک چند جمله ای، محاسبه مقدار یک چند جمله ای، ضرب و تقسیم چند جمله ایها، مشتق چند جمله ای و نیز منحنی رگرسیون چند جمله ای را محاسبه نماید.

تعریف چندجملهایها:

مثال: برای تعریف چندجمله ای

p(x) = x٣ -٢x +5

» p=[1 0 -2 5];

ریشه های یک چند جمله ای:

ریشه های یک چند جمله ای را می توانید به صورت زیر بدست آورد:

» r=roots(p)

r =

-۲٫۰۹۴۶

۱٫۰۴۷۳ + ۱٫۱۳۵۹i

۱٫۰۴۷۳ – ۱٫۱۳۵۹i

تابع polyval مقدار چند جمله ای را در هر نقطه محاسبه مینماید. برای مثال مقدار ( ۵p( به طریق زیر محاسبه می گردد:

» polyval(p,5)

ans =

۱۲۰

ضرب و تقسیم چند جمله ایها

برای ضرب و تقسیم چند جمله ایها می توانید توابع conv و deconv را بکار ببرید.

» a=[1 1 1]; b=[1 -1];

» c=conv(a,b)

c =

۱ ۰ ۰ -۱

مشتق چند جمله ای

مشتق چند جمله ای را می توانید با بکار بردن تابع polyder محاسبه کرد:

» c=polyder(a)

c =

۲ ۱

رگرسیون منحنی چند جمله ای

تابعpolyfit ضرایب بهترین چند جمله ای را پیدا می کند که از میان مجموعه نقاط داده شده عبور می نماید.

» x=[1 2 3 4 5];

» y=[5.5 43.1 128 290.7 498.4];

» p=polyfit(x,y,3)

p =

-۰٫۱۹۱۷ ۳۱٫۵۸۲۱ -۶۰٫۳۲۶۲ ۳۵٫۳۴۰۰

عدد ۳ در تابع نشانگر درجه منحنی رگرسیون است.

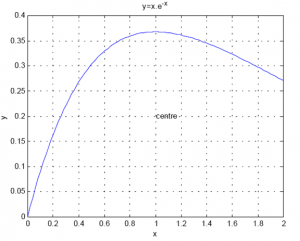

رسم نمودار

» x=linspace(0,2); y=x.*exp(-x);

» plot(x,y)

» grid

» xlabel(‘x’)

» ylabel(‘y’)

» title(‘y=x.e^{-x}’)

» text(1,.2,’centre’)

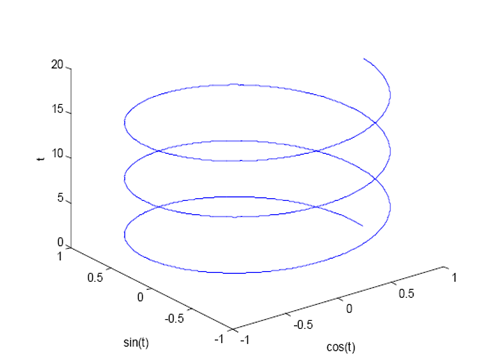

دستورهای زیادی در MATLAB برای ترسیم نمودارهای سه بعدی وجود دارند. یک منحنی سه بعدی را می توانید به کمک دستور Plot3رسم کنید:

» t=0:.01:6*pi;

» plot3(cos(t),sin(t),t)

» xlabel(‘cos(t)’)

» ylabel(‘sin(t)’)

» zlabel(‘t’)

(m-files) برنامه نویسی

m-file ها می توانند به دو شکل برنامه اصلی و تابع باشند. برنامه اصلی عبارتست از مجموعه ای از دستورها که می توان آنها را بطور جداگانه در محیط کارMATLAB اجرا نمود. هنگامی که نام برنامه اصلی را در محیط کار MATLAB بنویسیم این دستورها به ترتیب اجرا می گردند. به عنوان مثال برای محاسبه حجم گاز کامل، در دماهای مختلف و فشار معلوم، دستورات زیر را در ویرایشگر MATLAB نوشته و سپس تحت عنوان pvt.m ذخیره میکنیم:

% A sample scritp file: pvt.m

disp(‘ Calculating the volume of an ideal gas.’)

R = 8314; % Gas constant (J/kmol.K)

t = …

input(‘ Vector of temperature (K) = ‘);

p = input(‘ Pressure (bar) = ‘)*1e5;

v = R*t/p; % Ideal gas law

% Plotting the results

plot(t,v)

xlabel(‘T (K)’)

ylabel(‘V (m^3/kmol)’)

title(‘Ideal gas volume vs temperature’)

پس از ایجاد پرونده pvt.m برای اجرای آن کافی است که نام آن را در محیط کار MATLAB نوشته ونتایج را مشاهده مینماییم (نمودار رسم نشده است):

» pvt

Calculating the volume of an ideal gas.

Vector of temperature (K) = 100:25:300

Pressure (bar) = 10